From Business Requirements to Production Code

Here at Studitemps, we have to comply with many rules and regulations that we have to be certain are followed by our software as well. These business requirements have to be poured into production code 1-to-1. Otherwise, we risk losing our students, customers, and at worst, our license.

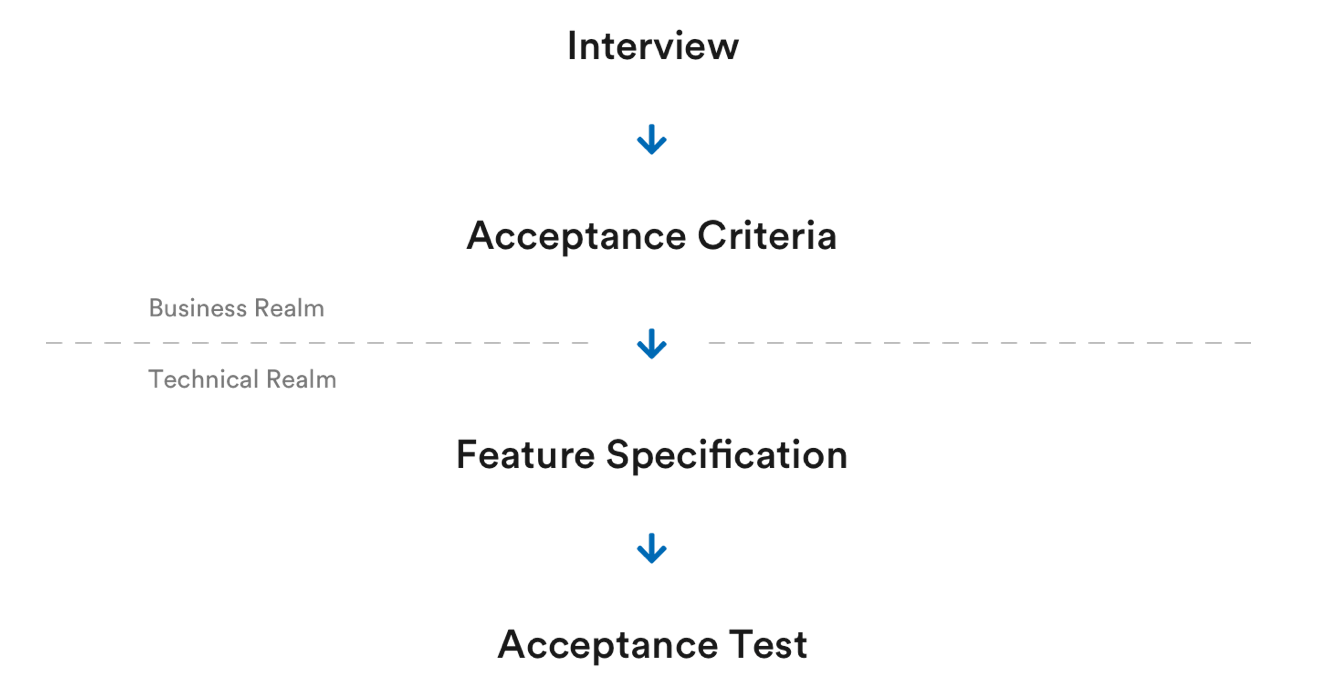

Therefore, we have to make sure that our software behaves in certain ways. We have developed a process of extracting and implementing business requirements and to make sure that our software will always operate as needed, even when we develop our software further.

The Interview

Before we can implement business requirements, we have to understand exactly what they are. For that, we interview our stakeholders about their needs. Talks like this tend to start with a concrete solution idea with which the stakeholder comes into the meeting. The goal of the interview is however to first understand the problem that we need to solve and only then are we brainstorming about potential solution ideas.

We took this approach from Domain-driven Design in which one should first explore and understand the problem space, before moving on to the solution space, in which solutions to the problem are developed. This approach has the advantage to engage every team member in the problem-solving process. If every member understands the problem the team is likely to develop many more and better suited solutions to the problem since the team members can employ their unique experience and background to find good solutions.

While interviewing the stakeholders, we tend to use a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions leave room for elaboration and mostly start with “Why”, “What”, or “How”. They are useful to gain an overview of the problem and to let the stakeholders explain in great detail what they need. If we believe that we have understood the problem, we use closed-ended questions, to verify our understanding. We use closed-ended questions only seldomly however since a simple “yes” or “no” from the stakeholders risks losing a lot of information about how much the stakeholders agree or disagree with a statement. We try to use estimations instead, like “From 1 to 10, how much do you agree with this statement?”.

Another principle of Domain-driven Design that we employ is Ubiquitous Language. It is hard enough to develop a shared understanding of a problem but it becomes much harder, if different words are used for the same thing. Therefore, we try to establish a common terminology that everybody adheres to. This language should also be specific rather than general. Whereas “personal data” can mean lots of things, “contact information” is already much more specific.

Acceptance Criteria

After we have established what the problem is and how we are going to solve it, we write a specific acceptance criterion that helps us verify or refute that our system behaves in a way that was agreed upon with the stakeholders. The criterion is written without code, but in the language shared with the stakeholders. In our case, this means writing the criteria, tests and even the code itself in German since all communication with stakeholders and within the team is in German. Therefore we opted to use the same terms and language on all levels of the development process.

An acceptance criterion can be rather trivial like “A user can create an account”, to very specific like “The wage bonus of hours worked on Sundays is exempt from taxation.” The purpose of acceptance criteria for us is to specify a behavior that the system has to show and to share that understanding with everybody involved. This approach is directly taken from Behavior-driven Development which focuses on “what” the system does instead of “how” it does it. Prioritizing the “what” over the “how” weakens the fallacy of letting personal interests influence what is built. If one is interested in the latest framework, which everybody talks about, user stories that might involve implementing this framework become magically much more interesting. However, the main goal is to fulfill the needs of the stakeholders and not one’s interest in technical advancements.

Feature Specification

Once the acceptance criteria are defined, we move to the technical realm and write our first high-level test. To make sure that the system’s behavior follows the business requirements closely, we write a feature specification first, typically using Gherkin syntax. For example:

Scenario: Taxation of Wage Bonus

Given an employee has worked on a Sunday

And has received a wage bonus for that work

When the taxation for that work is calculated

Then the wage bonus is exempt from taxation

We make sure that we don’t use technical terms in our specification. Steps like “The user clicks the ‘Register’ button” are dependent on the current state of the system. Once that state changes (e.g. the “Register” button is renamed to “Sign-Up”), we would need to adjust our specifications to reflect that change. A more change-resistant option would be: “The user creates a new account.” We like our high-level tests to be long-lived and independent of the implementation so that the behavior of the system is always checked in the same way.

Acceptance Test

Once the expected behavior is defined with a feature specification, we start writing acceptance tests. Whereas acceptance tests can be written on any testing level (i.e. e2e, integration or unit), we like them to be the most high-level automated tests we have in our system. Since acceptance criteria are checked against the system as a whole, it made sense to us to write automated tests that operate on the same level of abstraction.

We try to optimise the acceptance test for readability and to keep every test step as concise as possible. Most functionality is wrapped by helper functions whose function names give an explicit description of what the wrapped code is supposed to do. When the purpose of code is kept implicit, its purpose becomes an assumption, which varies with every developer who reads the code. By making the purpose explicit, the developer has a clear statement of purpose and can verify or refute whether the code is fulfilling its purpose against that statement. Let’s look at an example. The following code checks the last step of our feature specification. Please read it and be aware of how long it takes you to deduct the purpose of the code.

defthen “the wage bonus is exempt from taxation”, %{session: session} do

session

|> visit(“/pay”)

|> fill_in(fillable_field(“username”), text: “test-account”)

|> fill_in(fillable_field(“password”), text: “test-password”)

|> click(button(“Login”))

|> click(button(“Payslips”))

|> click(link(“01.11. - 30.11.2019”))

|> find(css(“#wage-bonus-taxation”))

|> assert_text(“0.00”)

end

The test code exposes a lot of details of how it asserts that the taxation is equal to 0.00. To understand it, you have to have a mental model of how the UI looks like. For example, did you notice that the test navigated to the “Payslips” tab and opened the payslip of last month given that this article was written in December 2019? The only critical line in this test is the line assert_text(“0.00”) since right here we test the behavior of the system of how to calculate the wage tax. Let’s look at the same test again, this time written with helper functions, which encapsulate most of the logic.

defthen “the wage bonus is exempt from taxation”, %{session: session} do

session

|> open_payslip_of_last_month()

|> assert_that_wage_bonus_taxation_is_zero()

end

This version of the test does exactly the same as the first version, but encapsulates any logic into helper functions, which define explicitly what they do. The test is much easier to read and to understand. If the developer cares about the underlying code, she can always dive into the helper functions which follow the single responsibility principle and do one thing only (e.g. login(), or open_payslip_from_november_2019()).

Summary

We started the process of bringing business requirements to our software in the business realm. We interviewed our stakeholders using open/closed conversation techniques starting in the problem space and slowly moving towards the solution space. We established a ubiquitous language to which everyone committed to adhere. Once a solution was agreed upon, we distilled the solution into an acceptance criterion, which gives our stakeholders explicit requirements against which they can verify the behavior of the system. The acceptance criterion focuses on the “what”, not the “how”.

Then, we left the business realm and moved to the technical realm. Here, we first wrote a feature specification, which is independent to technicalities and views the system as a black box. The specification was then tested in a concise acceptance test that moves the raw logic into helper functions, which explicitly describe the purpose of their implicit actions. This concludes the process of extracting business requirements and verifying them against our production code.